Editor’s Note:

This is the third and final article of a multi-part series on employee burnout in the restoration industry. Part one introduced the nature of burnout and summarized findings from a study on burnout in the restoration industry. Part two was a discussion on things restoration companies can do to manage one of the most complicating factors for burnout among restoration professionals – workload. Part three advances the conversation and discusses what restoration professionals can do at the individual level to manage workloads more effectively.

As we considered the findings of the burnout study and addressed hours worked, we first examined possible solutions focused on volume and capacity at the organizational level. When we consider the same dials of volume and capacity at the individual level, it is in the context of both the design of the operation and its culture. Individual volumes that allow for an optimal work-life balance will be contingent on a variety of factors that include but are not limited to capacity, competence, proficiency, efficiency, stress tolerance, focus, and organizational skills of the individuals. Although we consider adjusting the dials of volume and capacity at an individual level, this ability will be influenced by the culture and capabilities of the organization. There must be a level of personal responsibility for one’s own desire to find the proper work-life balance, commitment to the organization, and their individual roles. The company must share by supporting and creating a culture and operation that supports the adjusting of dials at the individual level.

Individual Volume

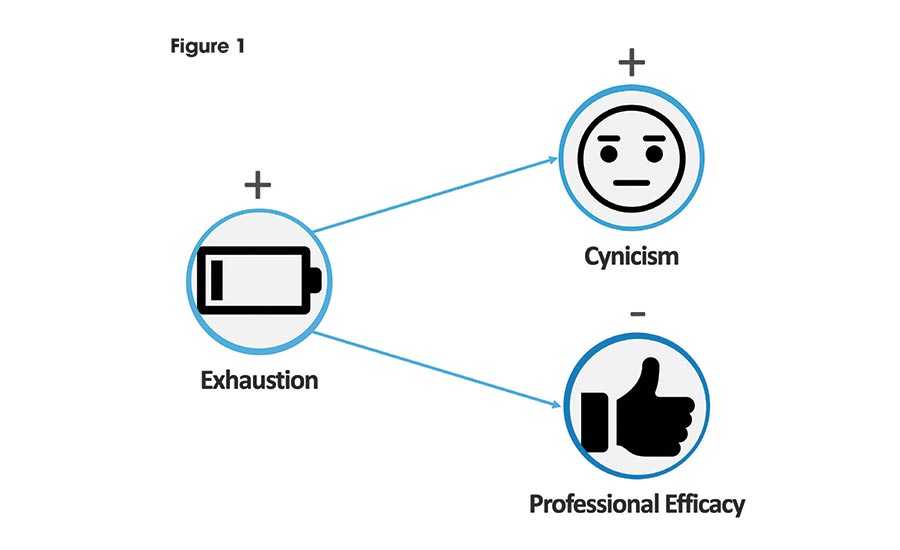

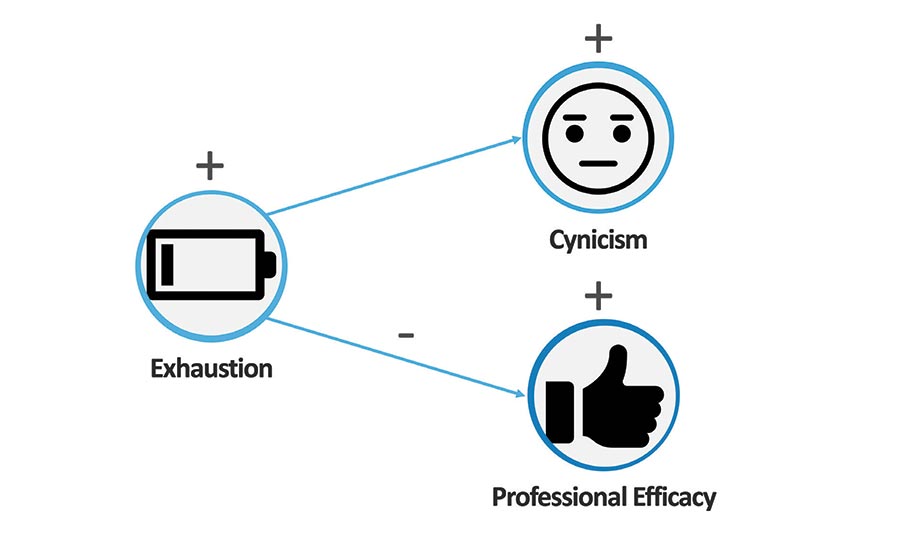

Due to the nature of the industry, one could say that a certain amount of flexibility and stress tolerance is a trait shared by many – restoration professionals appear to be highly resilient. At times, restorers may seem to be at their personal “best” when the chaos hits, and this may be supported by the finding that participants reported elevated feelings of professional efficacy while experiencing elevated feelings of exhaustion and cynicism – which is unique when compared to patterns in other industries.

1. Open Work Environment: Individuals and supervisors should have open communications regarding the volume of assignments.

Supervisor: “I have another job to go over with you”

Team Member: “I am feeling overloaded. I can take a new job next week but could really use a couple more days to get caught up”

Supervisor: “I will give it the job to Joe. Is there anything that I can do to help you?”

This comes with the caveat that managers need to be able to discern what volume a particular role should be able to manage and individual capacity. If someone has demonstrated they are not able to thrive under reasonable circumstances and with proper training, other options may need to be explored.

2. Assignments: The operation should be designed to manage assignment volume appropriately.

- It sounds simple but without accessible information and/or understanding of workflows within the company, it will be difficult to manage individual workflows. A simplistic example is to consider a CAT event. The workload first peaks in the field operations. Several weeks later, the peak in company volume may flow into the administrative functions and affect administrative workloads (bills, invoices, and collections).

- With the objective of assigning volume appropriately, we must understand the individual team member’s capacity and be mindful as we make assignments. We cannot arbitrarily make assignments based on job titles/descriptions. At any given point, we must consider the complexity of assignments and the individual’s capacity. For example, one team member may be able to manage 10 jobs effectively and another in the same position may be able to manage 20. A side benefit of this is that the company will likely be able to deliver services more consistently to the organization’s standards and objectives.

3. Workflows Adjustments: In consideration of the labor shortage and the fact that much of the workload within the restoration industry is technical and specialized, there may be an opportunity to control workload by challenging the current workflows and reassigning tasks. There are functions and flows within many parts of our organizations that require a combination of training and experience some of which are highly specialized. There are functions that may be easier to train and may have more accessible resources available. Workflow adjustments may be made within the organization as a response to workloads increasing for the individuals. As presented in Part 1, organizational level cross-training may give the ability to adjust workflows within, when deemed appropriate in controlling the workloads. An adjustment may also be approached by adding team members or outsourcing. Consider the following examples:

- Crew leaders and technicians are working a high number of hours. One of their responsibilities is to clean and restock the equipment after a loss. This function can be easily trained and facilitated by team members other than the crew leaders and technicians.

- Estimators are overloaded and one of their job responsibilities is to prepare the invoice. This is a part of their workflow that may be reassigned allowing them to contribute their specialized skill and relieving workload.

Individual Capacity

The organization must recognize the concept of capacity within the individual team members. A combination of encouraging, valuing, and investing in the development of individual capacity is a key ingredient to the ability to improve it. Individuals must take ownership of their capacity and understand the economics of it. It is in the best interest of individuals and the organization to increase individuals’ capacities. As one’s capacity grows, the individual can handle more work in less time, essentially reducing hours worked at a given volume of work. Individuals could also increase their value to the company. This basic principle can be observed in the practice of piece-rate work, where people are compensated based on output. Although the restoration industry does not lend itself to this method, the economic relationship between output and value is illustrated by it.

- Resourcefulness: By definition, resourcefulness is “having the ability to find quick and clever ways to overcome difficulties.” Be resourceful, challenge the status quo, and contribute to all aspects of adjusting workloads for you, for others, and for the organization. Applying resourcefulness includes but is not limited to evaluating and employing technology, evaluating workflows, finding new resources, and improving efficiencies.

- Management Principles and Work Habits: The organization should support, and the individuals can be driven to increase their capacity, by developing skills like time management, email management, and being organized. Consider the time wasted looking for supply, piece of equipment, finding an email, touching the same document 10 times before we act. There is an opportunity to increase our capacity and possibly reduce the inherently related stress by developing ourselves in these disciplines.

- Proficiency: The more proficient we are the more we can complete in a given amount of time. There are a variety of skills needed within a restoration company from monitoring a water loss to computer keyboarding. Companies should celebrate, develop, and encourage individuals to increase their proficiency in their skills and trades. In addition to executing our responsibilities with quality and consistency, we can grow and improve our proficiency in our skills and trades and be driven to do so. As an example, an estimator who is a novice will have to practice and be diligent, as a $5,000 estimate may take two hours to sketch and write. As proficiency is developed, the same $5,000 estimate may be completed in 30 minutes. At a given volume, the improvement in proficiency provided a net gain of 1.5 hours.

Organizations and their members can proactively manage volume and capacity to have a positive effect on the hours worked as a contributing factor to burnout within the industry.

As an industry, we can bring to the forefront the necessary skills, competencies, and practices that help its members enjoy the reward and opportunity offered. In consideration of the burnout study, by adopting these notions not only can we help professionals within our industry better enjoy the benefits and rewards of being a restoration professional there are additional benefits. In a time when finding new people to enter the industry is a challenge, we can better manage with the resources we have, we can help make our organizations stronger financially, and we can better serve those who call upon the industry in times of need. Beyond technical and soft skills, strategic operations, execution, workflow training, theory, and development can be actively pursued.

References:

Avila, J., & Rapp, R. (2019, January 2). Restoration industry burnout study. https://doi.org/10.5281/zendo.3404108

Bakker, A., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In C. Cooper, & P. Chen (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (pp. 37-64). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Deloitte. (2018). Workplace burnout survey: Burnout without borders. New York, NY: Deloitte. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/burnout-survey.html

Huberty, C. (1984). Issues in the use and interpretation of the discriminant analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 95(1), 156.

Lee, R., & Ashforth, B. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123.

Leiter, M., & Harvie, P. (1998). Conditions for staff acceptance of organizational change: Burnout as a mediating construct. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 11(1), 1-25.

Leiter, M., & Maslach, C. (2011). Areas of worklife survey: Manual (5th ed.). Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99-115.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (1997). The truth about burnout. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S., Leiter, M., & Schaufeli, W. (2016). The maslach burnout inventory: Manual (4th ed.). Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.

Maslach, C., Leiter, M., & Schaufeli, W. (2008). Measureing burnout. In Cooper, & S. Cartwright (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational well-being (pp. 86-108). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pines, A., Aronson, E., & Kafry, D. (1981). Burnout: From tedium to personal growth. New York, NY: Free Press.

Schaufeli, W., & Bakker, A. (2004). Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Preliminary manual (1.1 ed.). Utrecht, NL: Occupational Health Psychology Unit, Utrecht University.

Schaufeli, W., Salanova, M., Gonzalez-Roma, V., & Bakker, A. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a confirmative analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

Seashore, S., Lawler III, E., Mirvis, P., & Cammann, C. (1983). Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tonidandel, S., & LeBreton, J. (2013). Beyond step-down analysis: A new test for decomposing the importance of dependent variables in MANOVA. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(3), 469.

Wigert, B., & Agrawal, S. (2018). Employee burnout, Part 1: The 5 main causes. Washington, D.C.: Gallup. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/237059/employee-burnout-part-main-causes.aspx